|

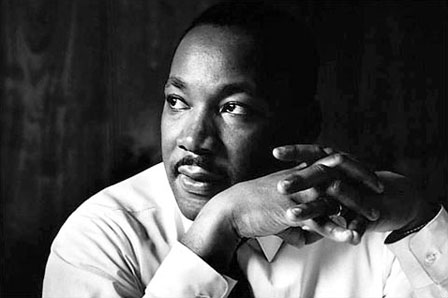

| Virginia Wolf with her parents. |

“Grief turns out to be a place none of us know until we reach it. We anticipate (we know) that someone close to us could die, but we do not look beyond the few days or weeks that immediately follow such an imagined death. We misconstrue the nature of even those few days or weeks. We might expect if the death is sudden to feel shock. We do not expect this shock to be obliterative, dislocating to both body and mind. We might expect that we will be prostrate, inconsolable, crazy with loss. We do not expect to be literally crazy, cool customers who believe their husband is about to return and need his shoes.”

― Joan Didion, The Year of Magical Thinking

I haven't yet found a way to share that I study death and dying without people asking (1) won't you get burt out? (2) isn't that depressing? and/or (3) how many people have you seen die? Each of these questions are a reminder of the reality that death is not only one of society's biggest fears but also one of the biggest unknowns. In fact, Geoffrey Gorer (1965) noted that death has become the new "pornography" having replaced sex as the societal taboo.

However, as Didion explains, we all anticipate that someone close to us will die and yet, working through the challenging emotions can leave us frozen in fear of the unknown. My explanation to each of the questions above is simple, I study the life right before death and the life that follows the passing of a loved one. It is too easy to get hung up on the end result; the eminence of death. Unfortunately, we forget or we just don't know the beautiful way in which the end of life leads to these rare moments of emotional clarity no different from the first time a parent sees their child. Furthermore, we forget that after death comes a new adventure discerning the ways in which we can build a relationship with our loved ones despite their passing.

In Moments of Being, Wolf describes her mother's death as "the greatest disaster that could ever happen." And I think, many of us can relate. When we lose someone dear, it is difficult to imagine the relationship changing, the thought of not talking to them as we always have. But despite religious beliefs or personal ones, it is clear that establishing a relationship after the loss of a loved one is necessary to find meaning and to wrestle with their loss. Fortunately in choosing to study death and dying, I get the rare opportunity to create opportunities to dignify the lives of those that we love. And perhaps, even more so, to dignify the lives of those we have forgotten. For the people that navigate this world with no one beside them and also for those that will pass with friends surrounding them.